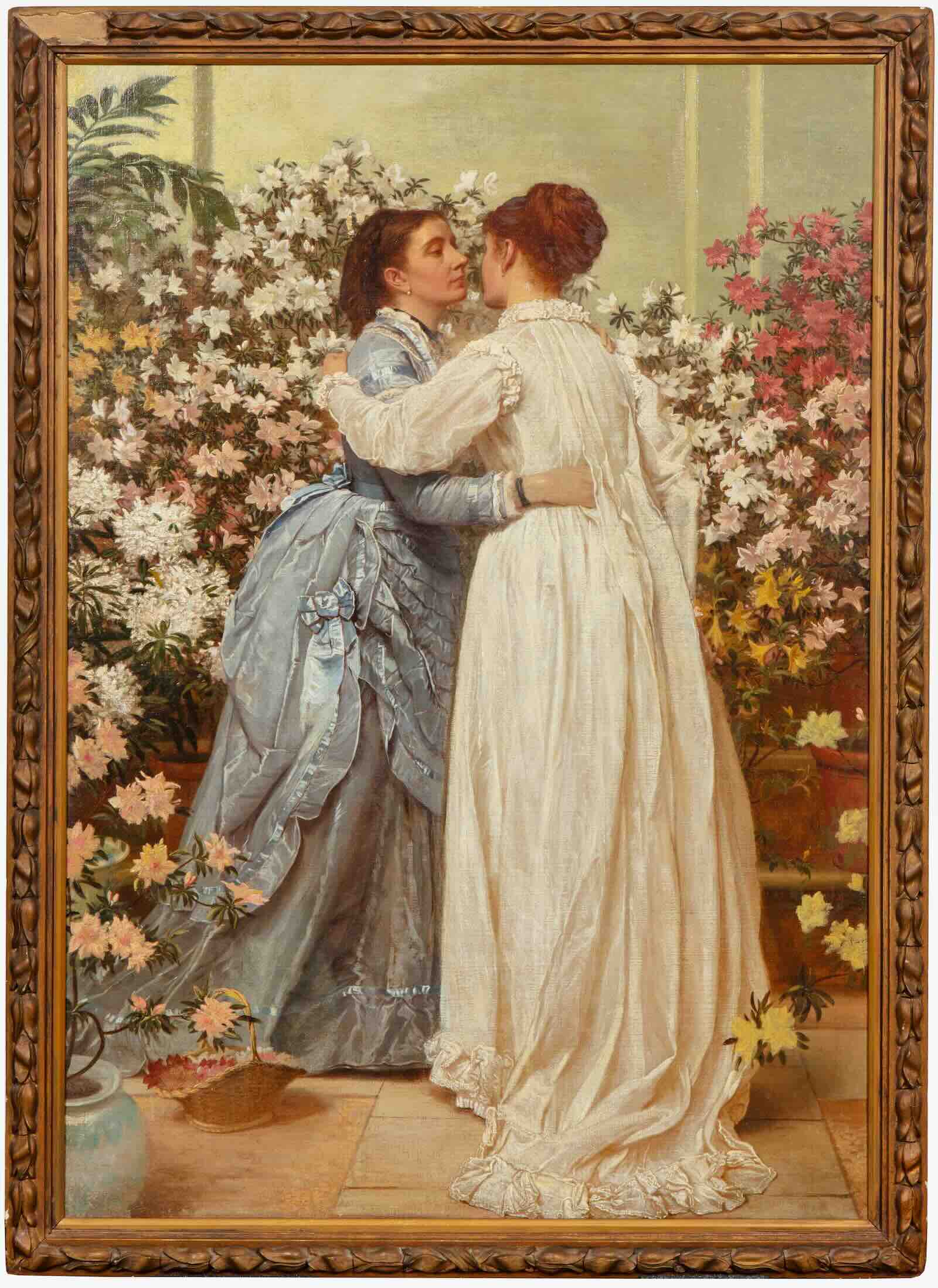

Also on display for the first time from today is a beautiful and little-known painting of Dickens’s eldest daughters Mamie Dickens and Katey Perugini, showing the two women embracing in the conservatory at home at his Gad’s Hill Place home, surrounded by flowers. The artist is unknown but the painting is thought to be by someone in the circle of Katey Perugini, herself an artist, and influenced by her style.

Charles Dickens published, collaborated, socialised, performed and lived with many independent, self-possessed women. At home, along with his children, Dickens shared his life with his wife Catherine and her sisters Georgina and Mary; in his work, he spent time with writers, reformers, philanthropists and campaigners. He was enlightened about women who were trampled by society and worked to improve the lives of homeless women, sex workers and prisoners.

Extra/Ordinary Women aims to reveal the influence and achievements of women often diminished in his books and in popular myth. The saintly Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) and the angelic Rose Maylie in Oliver Twist (1838) were modelled on Mary Hogarth (1819-1837), Dickens’s sister-in-law, whose untimely death at Doughty Street devastated the author. Dickens struggled to accept the loss, which could be traced in his writing for years afterwards.

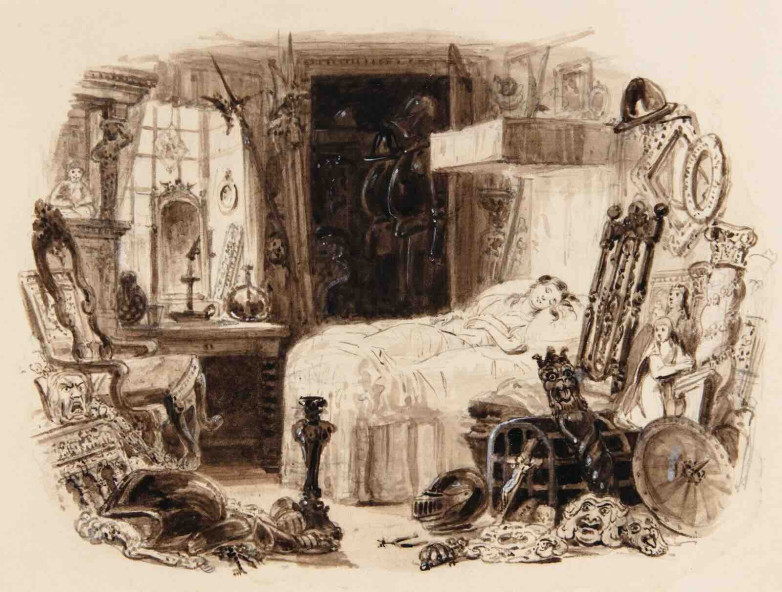

The exhibition features an ink and pencil drawing of Little Nell by one of Dickens’s illustrators, Samuel Williams, for The Old Curiosity Shop. Dickens advised Williams to make Nell look younger and more helpless. Meanwhile, the chaotic Mrs Micawber, also in David Copperfield, failed to capture the resourcefulness of her real-life inspiration, Elizabeth Dickens (1789-1863), the author’s mother. A significant item in the exhibition is a teaspoon from a set regularly pawned and bought back by Elizabeth as she fought to manage the family’s debts.

Sometimes, women were able to reshape their portrayal in Dickens’s novels. Jane Seymour-Hill (1806-60), Catherine Dickens’s chiropodist, a woman of short stature with the genetic condition achondroplasia (and a talent for slicing corns), became immortalised as Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield and argued successfully with Dickens to make the character more sympathetic and less grotesque.

Kirsty Parsons, curator at the Charles Dickens Museum, said: “Extra/Ordinary Women turns the spotlight towards a whole host of charismatic women who usually remain in the shadow of Charles Dickens. It reveals new sides to people who are often only mentioned in passing or seen through the prism of Dickens’s own views. We are pleased to be telling their fascinating stories here, in the home and neighbourhood which many of them knew so well.”